1- Beginning at Barking

The town which once boasted the largest fishing fleet in the world

is now unknown as a fishing port.

Indeed if you were to suggest to the average member of the public today that in the nineteenth century Barking was the most important fishing port in England then it is likely that they would be most surprised.

“First of the flood”

Barking, however, has a long history of fishing. The Thames was a fishery centre in the earliest days, favourable to both shellfish and whitefish, and the proximity of the country’s largest centre of population played a large part in its success. Fishing villages were to be found all along the shores of the Thames, supplying not only local markets but also riverside markets in London, including Billingsgate market which is of Roman origin (“Belin’s Gate” – this was the site of the first river crossing).

It is recorded in the Domesday Book that there was a fishery at Barking but it is possible that this was a fresh water fishery in the river Roding. At this time it is probable that the local people set fish traps in the river.

The earliest recorded mention of Barking fishermen was in 1320 when 16 nets belonging to men of Barking, Erish and Plumstead were seized because they had been used for catching undersized fish. Barking is again mentioned in 1349 when “Barkying and Grenewyche” fishermen were convicted of catching undersized fish on the east side of London Bridge. One G. Jackson relates that “John de Goldalone of Barking and two Greenwich fishermen was taken with 5 false nets and 3 bushels of fish too small for use. Being brought before the Lord Mayor they were remanded and it was ordered that the nets should be burned, the men being sworn not to use such nets in future and to find sureties for their good behaviour.” This was apparently not uncommon for in 1406 the Lord Mayor of London introduced minimum mesh sizes for nets used in the Thames and Medway.

It is believed that Barking men first fished to supply Barking Abbey, and after the dissolution of the abbey in 1539 they continued to serve the local populace.

In 1601 a Commission was appointed to investigate the condition of the Town Wharf, which was in need of repair. The subsequent report referred to “the trade of fishing beinge the onley staye and mayntenance of many”. Eight years later the ownership of the wharf had passed to the City of London Corporation.

Daniel Defoe mentions Barking in 1724, saying “Barking is a large market town, but chiefly inhabited by fishermen, whose smacks ride in the Thames at the mouth of the river Roding, from whence it (i.e. fish) is sent up to London to the market at Billingsgate, by smaller boats. These fishing smacks are very useful vessels to the public on many occasions as, particularly in time of war, they are used as press smacks, running to all the northern and western coasts to pick up seamen to man the navy when any expedition is at hand that requires a sudden equipment. At other times, being excellent sailors, they are made use of as machines for the blowing up of fortified ports and havens, as Calais and St Maloes.”

A newspaper advertisement of 1766 gives some idea of what the smacks were like at that time: “The smack Thomas and Elizabeth – now in the hands of Thomas Tyler, a prime sailor – river built, thirty tons or thereabouts, built with two and two and a half inch plank with scantling of timber in proportion, in very good condition: fit for immediate service and is as complete a vessel as goes on salt water. These kind of vessels are known to be the fastest shipping that swims.” Tyler was a man of some substance because he is quoted as saying that he had 40 smacks and another 17 or 18 building. A later Tyler was a notorious smuggler, working anywhere between Yarmouth and Falmouth up to the 1850’s.

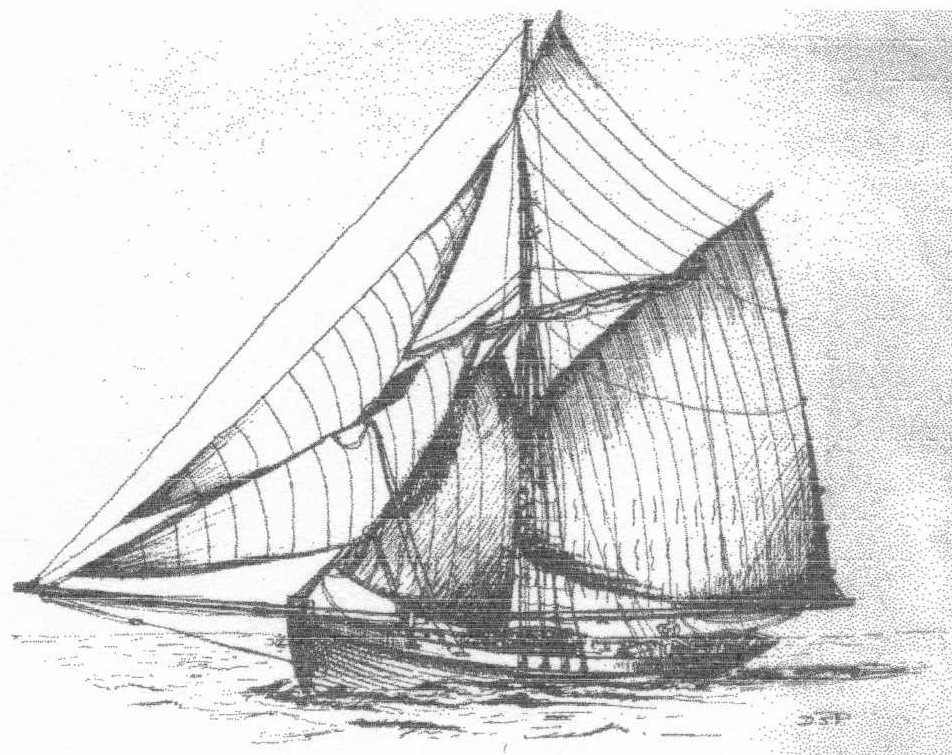

This sketch by DS Paterson gives an idea of what an early 19th Century smack looked like

At this time, Greenwich and Gravesend were also important fishing centres. In 1797 there were 120 fishing smacks of between 50 and 60 tons, and 17 hatch boats registered at Gravesend. Hatch boats were the small boats mentioned by Defoe for transferring the fish up to Billingsgate.

The centre of the cod fishery during the latter 18th century was, however, Harwich. Fishermen had been lining for cod from there for many years, and used vessels called well smacks. These vessels probably originated in Holland, but the first to be built at Harwich was launched in 1712. These vessels contained a tank in which the fish could be kept alive to keep them fresh. By 1735, there were 30 of them. In 1766 the first trip longlining on the Dogger Bank was very unsuccessful, but they persevered and by 1798 there were some 96 codsmacks. It was about this time that similar vessels began to be built at Barking, Gravesend and Greenwich, and Harwich began to decline as a fishing port.

These vessels were purely line fishing boats. Trawls had, however, been used by Barking men for centuries – there was considerable trouble in the early 1630’s when they were several times accused of using trawls with undersized mesh off the Kent coast. A 1750 account of a Barking Cod Smack gives the weight of a pair of “troylheads” as 1cwt 0qt 20lb, and the size of the trawl warp as 4½ inches which would indicate a small trawl with a beam length of probably less than 20ft – but deep sea trawling came to Barking in the late 18th century. The Barking fishermen began to use the welled smacks for trawling as well as for lining, and would change methods according to the season.

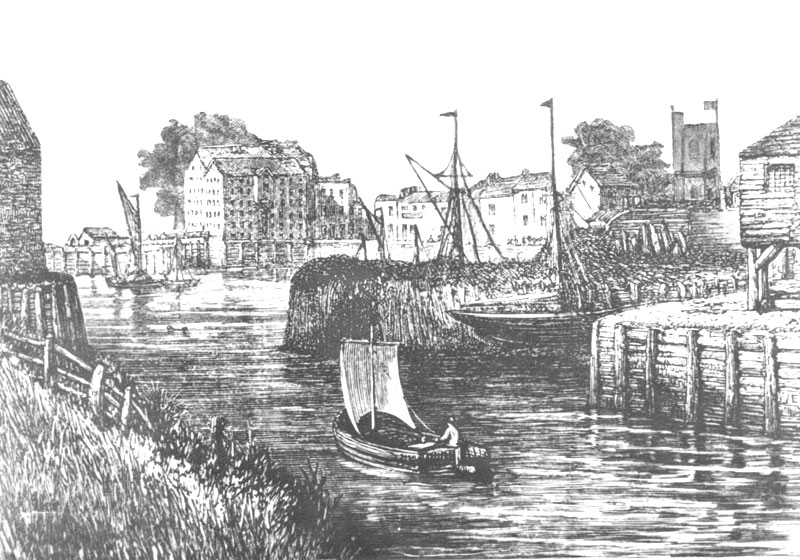

Barking Pool c1800, drawn by A B Gilderson

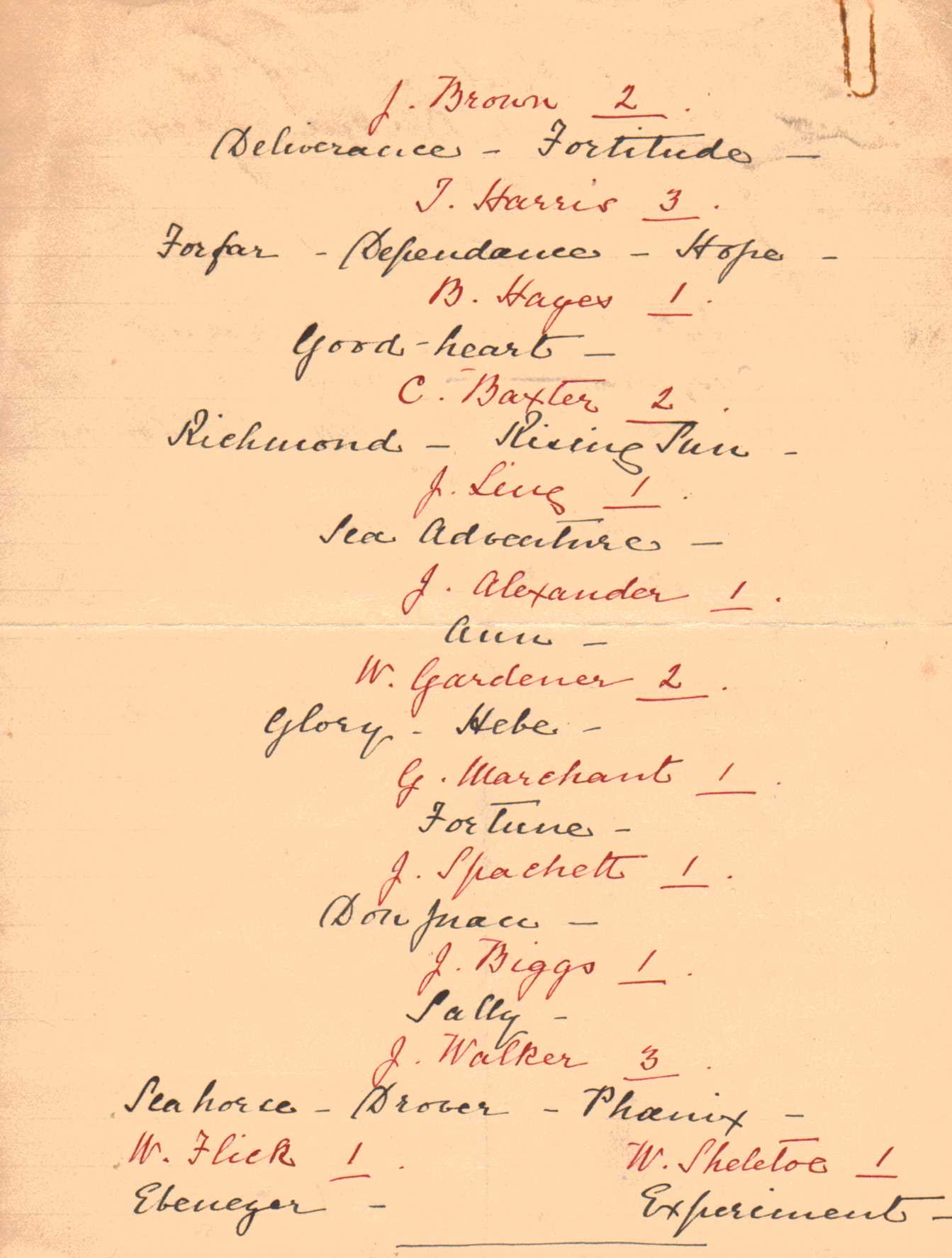

In 1800 the following evidence was given by Thomas Tyler to a fisheries commission:

“We catch thornbacks, maids, and other flatfish on the Sands, called the Brown Bank off Yarmouth, the Broad Fourteens, and Smiths Knowl, where there is a prodigious quantity of fish. We have 40 sail at Barking constantly employed in that fishery, they sometimes bring such a quantity of fish to market that they cannot be disposed of. They are sometimes sold as cheap as one shilling a basket of 20lbs. At this season, the plaice, maids and haddocks are in prodigious quantities all the way from Lowestoft to the Dutch coast. Soles will succeed them, and at the latter end of the year, haddock.”

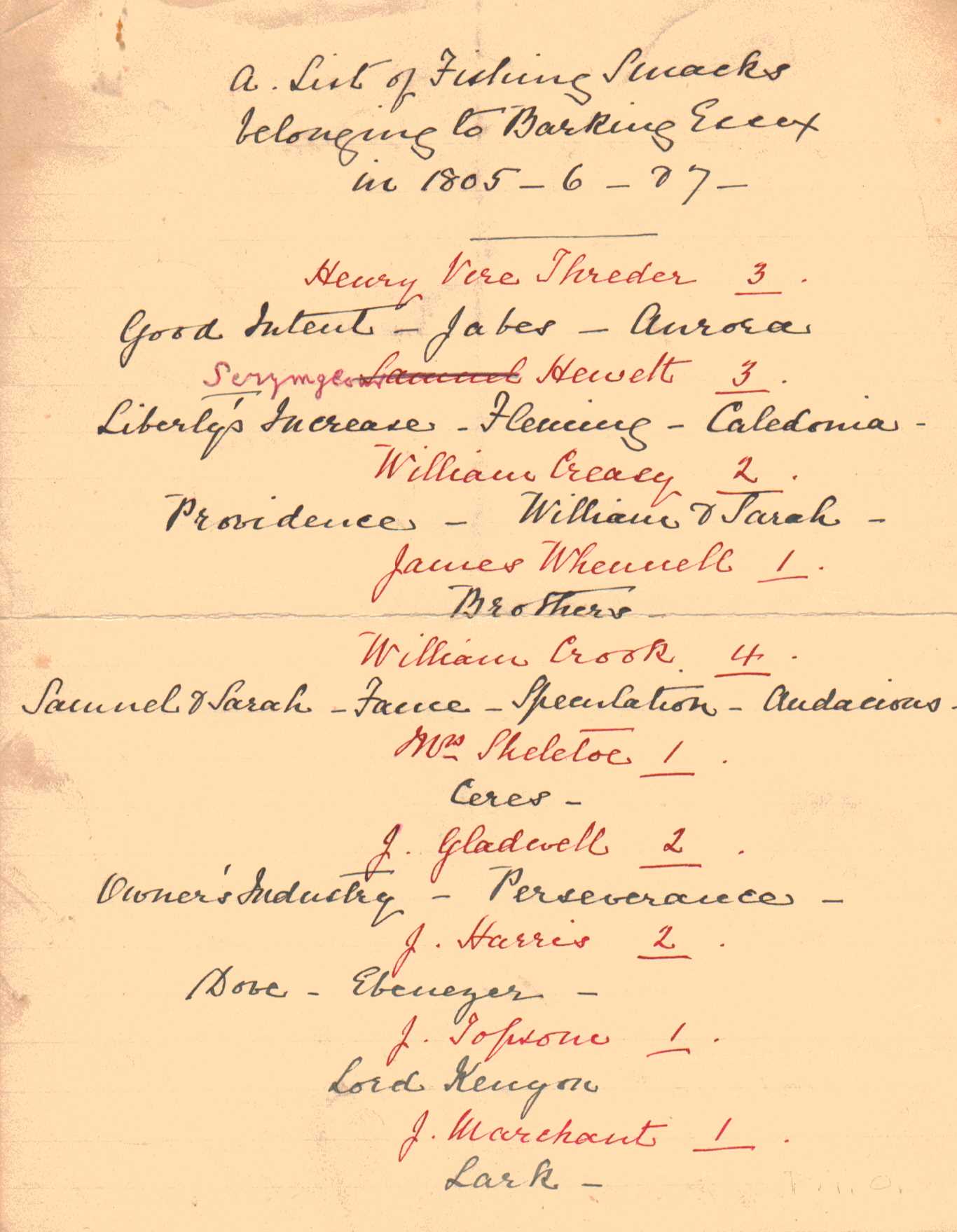

Local records show that there were 23 smackowners in Barking in 1805 and that between them they owned 40 smacks.

It was into this environment that Scrymgeour Hewett (1765-1850) had moved in about 1795. His father, Dr Alexander Hewett, died in Scotland in 1773, and his mother moved to London with six children six months later from Cupar in Fifeshire. Scrymgeour went to the West Indies for a number of years before returning to London. He was reputed to have been sent at some stage to look after some property belonging to his aunt at Dagenham, but this land has not been traced.

Scrymgeour Hewett 1765 – 1840

Whatever path his life took, he ended up at Barking which he reputedly described as “the prettiest village I have ever seen”. This judgement may have been something to do with one Sarah Whennel, the daughter of a local smackowner. Scrymgeour subsequently married Sarah at West Ham in 1797 and went into business with his new father-in-law, James Whennel. James owned two smacks, one of which, The Brothers, he had owned since 1764.

Scrymgeour went to sea himself, but he was also a man of means and was therefore able to buy his own boats. He started with a vessel called the Liberty’s Increase. After a short time he added the Fleming, Caledonia, Matchless and Fifeshire, all 40-60 tons well smacks. The Napoleonic Wars broke out at about this time, and it is said that he owned a letter of marque brig, which he lost. It is known that Scrymgeour subsequently built a ship called the Fifeshire which was pierced for guns, but whether this is the same vessel as the fishing smack it is unclear.

Scrymgeour lived at Fawley House, East Street Barking. Fawley House still stands today.

Scrymgeour had several children, of whom something is known of some of them. The eldest, Fleming, became a banker. The second son, Samuel, was born on December 7th 1797. Apparently Scrymgeour would have liked him to go into banking as well, but Samuel had different ideas. While Scrymgeour was away at war in the Fifeshire Samuel ran away to sea in one of the other smacks. Consequently, on his return, Scrymgeour had the boy apprenticed to himself – the Indenture is dated 3rd April 1812 so Samuel was 16 years old at the time. There is a record in the Press Protection Ledger that Samuel enjoyed protection from the press as a fishing apprentice aboard the Fleming in January 1812, some months before his indenture.

In 1811 there were said to be some 70 smacks at Barking, of some 40 to 53 tons.

The wars finished in 1815. Nearly all the local lads from Barking had been away at war and it is reported that the lanes in the area had all become overgrown and sometimes impassable.

Samuel took command of the Liberty’s Increase in 1816 and the Fleming in 1817, and consequently gained much first hand experience of the North Sea fishing grounds. To quote a note written by Samuel himself: “I went Master of the Liberty’s Increase 20th of June 1816. I was 18 years old 7th Dec 1815. I stayed in her till after Christmas then I went on board the Fleming to sail before the mast and I continued there till the 22nd of May 1817 then I went Captain of her to the Northwards for turboats. The first sharing we made we shared £91 11s a vessel for which my father paid me £5 that was the 31 of July.”

Samuel Hewett 1797 – 1871

A little is known of these two smacks. According to Samuel’s diary, the Liberty’s Increase was built at Gravesend by Gladwell for Scrymgeour and was bought by Samuel from his father in 1804 for £300 [he would have been 7 at the time]. The Fleming was built in 1801 at Cowes for Scrymgeour, and Samuel bought her in 1824 for £500. Both were well smacks. To give an idea of running costs the Liberty’s Increase in 1830 “had new mast and new elm boat of Gladwell cost £15” and on Sept 20th 1834 “paid Knock £6 7s 0d for fouling bottom topsides and wellhead”. The account of Aid (below) is another insight.

The Fleming was sold in 1835 for £420 to a Richard Harvey; Samuel held a mortgage for £390 which was paid off including interest by 1839. Apparently the Liberty’s Increase gave 40 years good service and was then broken up and the stern rail placed in the garden of Fawley House – a small house in East St, Barking where Scrymgeour lived, which he had bought in 1822.

In 1825, Samuel “came ashore” and concentrated on running the business from on land. His father was sixty in this year so he would have likely wished to retire. In 1826 Samuel bought the lease of the slipway at Barking, and had the Nancy built at Strood. He sold fish at Billingsgate for the first time in 1827. For the next fifteen or so years he gradually bought and built more smacks, building up a respectable fleet. Some smacks he bought with or sold to other skippers, lending the skipper money as a mortgage. By the speed of expansion and his ability to lend money to skippers for the purchase of smacks, it is a reasonable assumption that he had a sound financial base, probably not derived from fishing.

Smack Aid build by Bankham at Finsbury

Nov 19th 1838 bought her of the mortgagee Mr Tyler for £370.0.0

Nov 19th To first purchase 370.0.0

To measuring and paper’s 5.0.0.

Bradstreet’s gift 27/6 my expenses 12/6 2.0.0

Compasses Spyglasses and hour glass 2.0.0

four ash oars 2.4.0

Joanes’s bill Spashett’s bill £21- 21.0.0

Harris do £12.0.0 Pearson do £22- 34.6.0

Ditchburn do 42.9.6 42.9.6

extry ballast 5.0.0

Caulker’s labour and Material’s caulking all over 16.0.0

New boat £15 Shipwright & ???? £30 45.0.0

Mainsail Foresail Squaresail Topsail Stunmesail [?]

& Jib’s over & above what Pd Harris 75.0.0

Rope Shrouds Stay & Spunyarn 22.10.0

Netts & Trals gear 35.0.0

Smoaking cleaning and fitting out in Dec & Sundries

& running ropes 22.10.0

£700.0.0

1839 Dec 7th Smack Aid Sailed to Holland on my account Joseph Bass Master

1840 June 8th Sold the Aid, to Willm Hale for £550, Hale paid £150, my Father paid £200.0.0, and I lent him £200.0.0 that’s a mortgage for £400.0.0 being for £200.0.0 for my father, and £200.0.0 for myself. W Hales is to pay my £200.0.0 first and then my Farther’s £200.0.0 with 5 per cent Interest, on the £400.0.0

(Extract from the Ledger of Samuel Hewett)

The wood to build smacks and privateers at Barking came from Hainault Forest which in those days extended to within the Borough of Barking, and the trees were apparently pulled out by the roots. While supplies lasted, all frames and knees were “grown”.

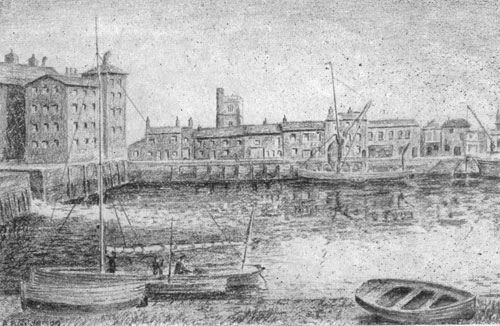

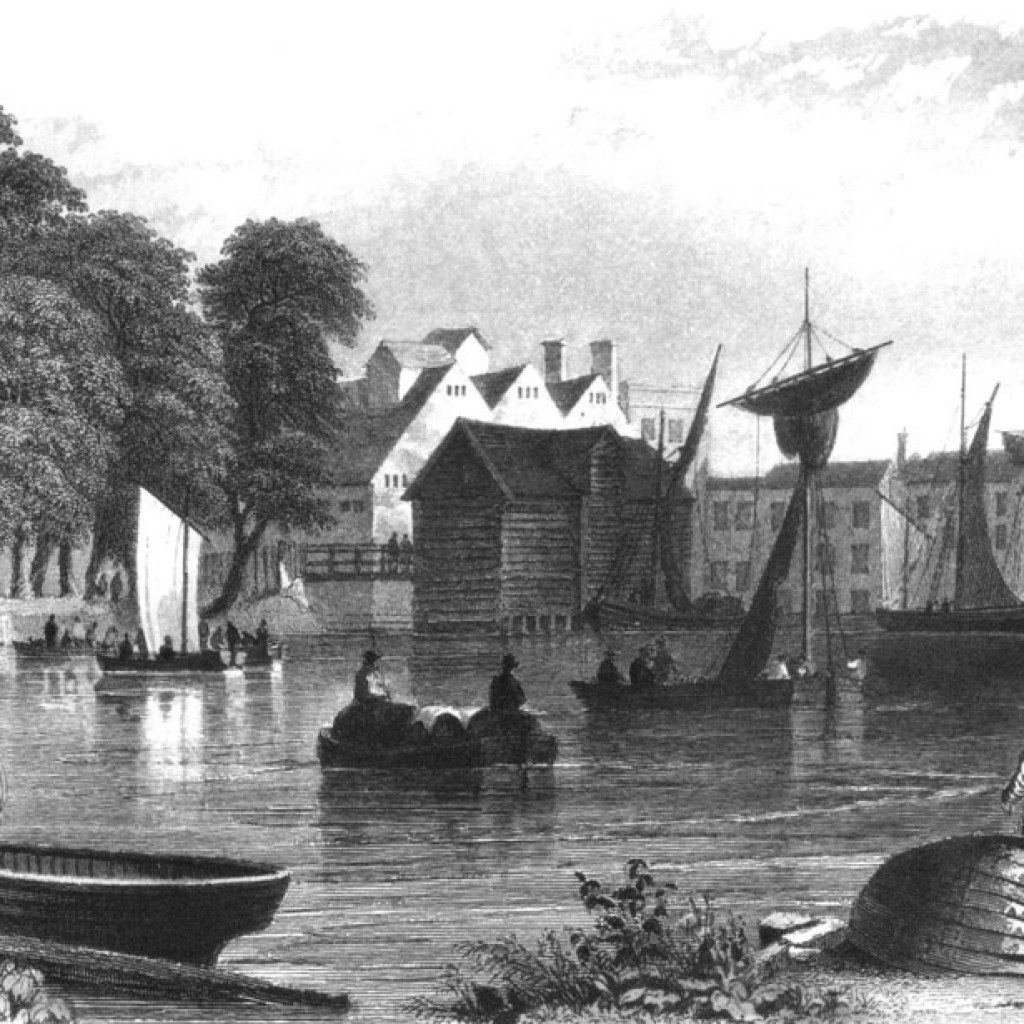

Barking Pool 1832, drawn by W. Bartlett and engraved by H. Wallis

In 1833 Samuel gave evidence before a Select Committee set up to investigate the British Channel Fisheries. He said that the fishing from Barking had not been successful for several years. He said that he had left the sea about eight years before (i.e. 1825) and owned now “six smacks of his own on shore and four others”, of the 120 in total at Barking, each of which averaged 50 tons. [Fishing can’t have been too bad as he had bought 2 of these 10 this year]. When questioned as to foreign interference he said that he had never found any opposition to fishing in Dutch waters but they seldom went within 7 miles of the coast. A friend of his had been forced to shelter in Texel when his smack broke her mast, and having no provisions or money he sold a few fish and this cost him £9 10s before he was permitted to leave harbour. Yet thirteen Dutch vessels were constantly landing turbot at Gravesend, making three or four voyages with about twenty score of fish in each boat. His smacks were licenced to carry a crew of 9 and they made two to three voyages a month in winter, returning with fish from “half-seas across off Yarmouth”. They did no trawling off the Lincolnshire coast as they fished there for cod with longlines, these cod voyages lasted about a month and after lining for three months the smacks returned to trawling. He reckoned that if his fish was not at Billingsgate by 8 a.m. the market was over.

When lining, the crews needed light to be able to see the hooks, so these trips were undertaken in the summer. In the winter the trawled fish, some of which came up suffocated, would keep longer in the cold weather.

In March 1835 Samuel bought the wharf and shore belonging to J. Brown for £1620, houses in Fisher Street from W.Harvey for £631.10.0, and a sail loft and boathouse for £200. To this he added in 1842 the wharf and shore belonging to J. Brown on a 99 year lease for £30 per year, and in 1844 the wharf and ways adjoining on a 99 year lease at £12 per year.

In 1839 there were some 133 smacks of 50-60 tons burthen at Barking. The pool at Barking was a natural dry dock with access at high tide leaving enough time at low water for repairs and scrubbing to occur. The smacks had to sail up the Roding but local men who were often old fishermen known as “bobbers” would tow the vessels when necessary. If the wind was strong northerly or the tides particularly neap then the smacks would have to wait outside in the Thames, and the bobbers would take things to and from them, and tend to their lights if needed.

It is also interesting to note that in the early half of the nineteenth century there were only two buoys in the Thames; one at the Nore and the other at Blacktail Spit. These were of course not lit at night. Navigation must have been very difficult in the dark or indeed in fog or poor visibility as the only way forward was by judicious use of the lead, as the sandbanks of the Thames often shift.

The 1841 census showed that there were 20 shipbuilders, 6 mastmakers, 7 blockmakers, 24 sailmakers, and 12 rope and twine makers at Barking.

By 1840 the population of London had exceeded two million, having risen sharply from 657,000 in 1750, a mere ninety years before. With the demand for fish exceeding supply, the industry for ready for expansion.